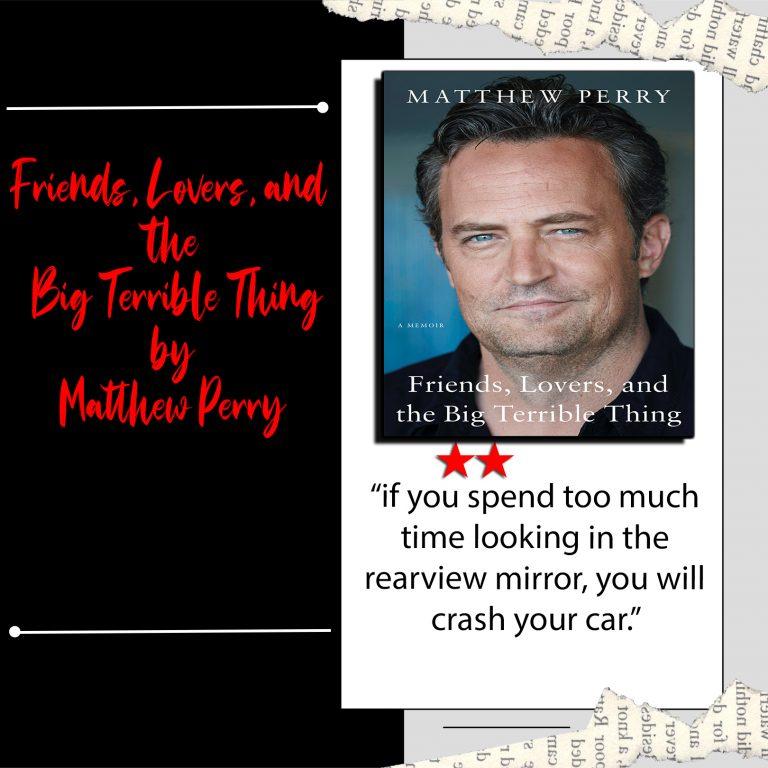

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing A Memoir by Matthew Perry

Friends in Low Places

As an ardent Friends fan, my anticipation was palpable when I decided to give this a try. However, as I reached the end, all I wished for was to reclaim the six hours I had spent listening to it. In the grand scheme of things, the disjointed timeline in this book didn’t particularly bother me, although I can imagine that a chronological order would have made it a more enjoyable read. However, given the content and tone, “enjoyable” isn’t the first word that comes to mind when describing this book.

The book appears to suffer from poor editing and doesn’t portray Matthew Perry in a very positive light. His journey through addiction is depicted with honesty, rawness, and a painful intensity that makes it difficult to listen to or read. I do give him credit for putting it all out there, and I sincerely hope it serves as a form of healing for him. Nonetheless, it’s clear that he is battling dopamine addiction, and there’s a suspicion that the primary purpose of this book might be to feed off the attention he’s currently receiving. Once the initial surge of attention from the book release subsides, there’s a concern that he might seek another form of high and potentially relapse.

Throughout the book, there are noticeable inconsistencies in his story and journey. For instance, he initially states that he has all his necessary supplies, including cigarettes, but later devotes an entire chapter to quitting smoking. Furthermore, he has publicly claimed to be “pretty much sober since 2001,” except for the 64 relapses, which feels like an unnecessary and potentially misleading assertion.

One of the most challenging aspects of the book is the impression that he hasn’t truly grasped the lessons life has to offer. Reading this book made me reflect on the developmental damage caused by adolescent alcoholism to the brain. It appears that Matthew Perry may not have developed the critical thinking, coping skills, and empathy necessary to navigate adulthood effectively.

Considering his 30 years in therapy and attendance at 6000 AA meetings, his lack of insight and self-awareness is surprising. Overall, he comes across as a self-absorbed individual with limited empathy for those around him. While he claims to want his story to help and inspire others, the book doesn’t convey a strong sense of altruism or philanthropy.

Another aspect that left a sour taste was his portrayal of his father’s journey to sobriety. He suggests that his dad simply stopped drinking one day and didn’t require $7 million worth of treatment, highlighting that his father doesn’t have that kind of money. Given Matthew Perry’s substantial wealth, one would hope he’d support a family member in need, but this unnecessary dig at his father suggests otherwise.

Finally, his description of his treatment of women in his life was off-putting. While not abusive, it paints a picture of him using and easily discarding them. It raises questions about what he brings to a relationship beyond being Matthew Perry, hinting at struggles in forming meaningful connections, which is truly disheartening.

In conclusion, this book left me with the impression that Matthew Perry might be an enjoyable person to hang out with but lacks depth and substance. It’s also worth noting that even during his battle with deep addiction, he remained on the shortlist for guest spots on high-profile shows and was able to initiate projects, suggesting he’s likely easy to work with. However, it’s unfortunate that this book significantly diminished my opinion of this performer. If you’re interested in reading this book despite my impressions, feel free to click the link below and explore it for yourself.

Friends, Lovers, and the Big Terrible Thing A Memoir by Matthew Perry